Sitting pretty at the helm of League One, Wigan Athletic, with 15 of 23 possible clean sheets to their name, don’t have many concerns. The purpose of this article, however, is not to berate manager Paul Cook or the team, but to highlight why Wigan failed to create quality chances against Charlton, along with some potential solutions to inform Wigan’s approach against teams that set up similarly in the future.

Shrewsbury and Charlton gained success with their approaches, both setting up in an organised block (albeit quite differently), and other teams will have taken inspiration from this, now knowing the blueprint to earn a point against Wigan. Shrewsbury defended actively, forcing Wigan into traps and pressing backwards passes, while Charlton defended passively, setting traps but remaining happy to let Wigan circulate the ball around the backline without providing pressure until the ball entered midfield.

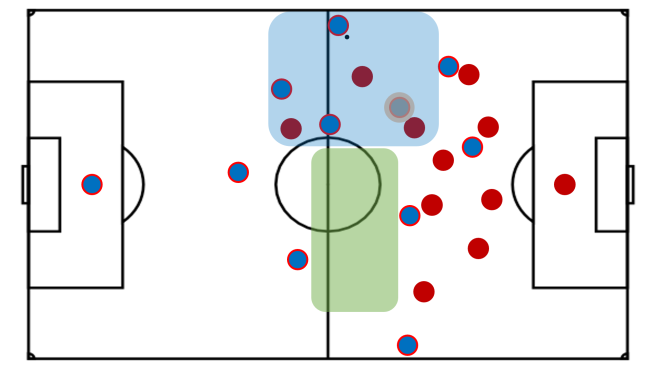

Wigan’s strategy to counteract Charlton’s passive approach was inefficient and ultimately led to Will Grigg feeding off scraps. Charlton defended in a deep 4-5-1 shape with an emphasis on protecting the centre by utilising a compact shape which spanned roughly the width of the penalty area, particularly uncharacteristic of a typical Karl Robinson side. For purpose of ease, Charlton’s compact shape will be herein referred to as a ‘block’.

Through sustaining a heavy central presence, Charlton forced Wigan to the wings due to a lack of free men available in the centre. As the ball arrived in wide areas, Charlton applied pressure quickly to stop Wigan progressing through their full backs or wingers, which meant the ball was either played back into defence or clipped down the line for someone to chase. More often than not the ball was played back to the centre back, and the same pattern would occur on the opposite side after a switch, which played firmly into Charlton’s hands.

Why, then, did Wigan struggle progress the ball through the centre more effectively? Although a compact low block is difficult to penetrate, there are ways of creating space within the block to allow for more dangerous central progression, but Wigan’s shape was not conducive to doing so. Generally, most of Wigan’s issues derived from a lack of occupation of the centre.

As per the diagram (above), the positioning of Wigan’s players is a concern. There was mostly only one player, Powell, positioned within the block, which enabled Charlton to achieve their goal of defending the centre with ease. Morsy and Evans, the two deeper midfielders, took up almost symmetrical positions in front of Charlton’s midfield, failing to threaten any central progression. If Evans or Morsy received the ball, they were in positions to be pressed quickly without much need for Charlton’s shape to become disjointed.

With no easy route to the centre, Wigan were forced to the wing, where Charlton set a pressing trap. Even when Wigan managed to beat the trap and progress down the wing, their lack of central presence limited them. Jacobs and Massey, when receiving the ball, often had no support from players inside Charlton’s shape, which left them isolated in unfavourable situations, leading to conceding possession or playing back into defence. A solution to this could have been that when one of Evans or Morsy dropped in front of Charlton’s midfield to receive, the other could take up a more central position. This would commit their opposing midfielder into a decisional crisis – press the player in front or focus more on blocking the passing lane to Powell? Either decision would benefit Wigan. Charlton’s midfield having to press the midfielder in front would open more space for Powell, and focusing more on blocking the passing lane to Powell would give Evans or Morsy more time with the ball to find a forward option.

Passing backwards isn’t as disadvantageous as it sounds, serving the purpose of starting a new attack, but slow, continuous ‘horseshoe’ circulation from one wing to the other through the defence is largely ineffective. Wigan would play 4 or 5 passes only to end up in the same situation on the opposite side of the field, while Charlton only needed to shift across the pitch without expending too much energy or opening any spaces in dangerous areas.

Another aspect of Wigan’s play that limited their ability to retain the ball high up the pitch was a lack of aggression from the full backs in their positioning. As Evans and Morsy often dropped into deep, wide positions between the centre back and full back to receive the ball under less pressure, Elder and Byrne could have positioned themselves further up the wing without risking too much defensive security. This would have allowed Wigan to use the wings effectively as a means of progressing play, however Elder and Byrne mostly received the ball in front of the opposing winger rather than beyond them, meaning the winger could easily force them back inside through closing the option down the line when pressing. By positioning themselves on the shoulder or beyond the winger, the full backs could have easily bypassed their respective opponent with their first touch.

Perhaps the conservative positioning of Elder and Byrne was caused by Wigan’s own wingers being positioned directly in a straight line ahead of them. Jacobs and more so Massey generally hugged the touchline, which might have prevented Elder and Byrne from being more aggressive as it would have resulted in them occupying the same space. A solution to this would be for the near-side winger to move infield and the near-side full back to get high and wide. To provide balance and defensive security in case of a loss of possession, the far-side full back could move infield while the far-side winger could stay wider.

Immediately, the near-side winger coming inside would provide Wigan with connections from the wing to the centre, which could result in the likes of Jacobs and Powell receiving the ball behind the opposition midfield, which is exactly where you want them to have possession. A final pass to get Grigg in behind would have a higher chance of success if it came from just in front of the defence in the centre, rather than from deep or out wide. Due to the improved connections across the pitch, with shorter distances between players and a stronger occupation of the centre, Wigan would have more chance of retaining the ball in dangerous areas. Having more players positioned within Charlton’s shape rather than around it would have forced many more decisional crises from the away side, which would have likely led to more defensive errors from them and would have helped to create free men in dangerous areas for Wigan.

From the suggested changes, Wigan would have more clear routes to progress play upfield. The higher positioning of Elder and inside positioning of Jacobs would allow Wigan to overload Charlton’s right back, and the short option provided by Morsy would likely attract pressure from Charlton’s midfielders, opening vital space between the lines. By having players positioned between the lines, Wigan could switch the point of attack in more dangerous areas and, if done quickly, could potentially get Massey 1v1 on the right. Even if switches occurred across the backline, the shorter distances between players would ensure that the tempo of Wigan’s play could remain high.

From the suggested changes, Wigan would have more clear routes to progress play upfield. The higher positioning of Elder and inside positioning of Jacobs would allow Wigan to overload Charlton’s right back, and the short option provided by Morsy would likely attract pressure from Charlton’s midfielders, opening vital space between the lines. By having players positioned between the lines, Wigan could switch the point of attack in more dangerous areas and, if done quickly, could potentially get Massey 1v1 on the right. Even if switches occurred across the backline, the shorter distances between players would ensure that the tempo of Wigan’s play could remain high.

This was another key issue in the match, in that Wigan’s slow circulation of the ball made it extremely easy for Charlton to defend passively, shifting side-to-side. The reason for the slow tempo was mainly due to Wigan’s shape, as the distances between players were large and thus passes were slower, and the receiver of the ball therefore struggled to use the weight of the pass to take a positive first touch forward.

A further issue was the lack of rhythm changes in Wigan’s possession. When, for example, Wigan made some spatial progression by switching play to Elder, the benefits of this were lost as he took too many touches and Charlton’s players could adjust their positions accordingly. Faster circulation, though, is facilitated by each player having multiple options in possession, something which Wigan struggled to establish throughout the match. Taking advantage of being able to progress into open space with the ball is a key factor in creating chances, particularly against teams that defend in a low block due to the limited amount of space that becomes available during the match. Taking fewer touches or larger touches can be the difference between beating an opponent 1v1 or having to turn back to play into defence.

All was not lost, however, and Wigan did get some success on rare occasions when Evans committed his man through dribbling with the ball. If a team struggles to create free men through their positioning (i.e. between the lines, creating triangles), dribbling can be crucial to freeing up a teammate as it forces the opponent(s) to decide whether to press or drop, either of which cedes space and time. However, Wigan rarely took advantage of this, likely due to the deep, wide positioning of Evans and Morsy as it is a difficult position to dribble from, and the risk of losing the ball with little protection behind them might have arguably outweighed the benefit of freeing a teammate up.

Wigan’s inefficient approach led to a change of strategy as the match grew on, with Cook bringing on Ivan Toney and Noel Hunt to give Latics more presence up top. Whilst I would argue that a front three of Grigg, Toney, and Hunt doesn’t contain suitable personnel to gain success from playing long balls to, particularly against a tall defence, Wigan created a couple of chances through Cook’s changes. Until Toney and Hunt’s substitution, Wigan lacked runs in behind. Due to their inherent danger, runs in behind force the defensive line to drop, and can lead to chances close to goal, space created between the lines if midfielders don’t drop, and can force the whole unit further back. Wigan struggled to get the likes of Powell and Jacobs facing forward in dangerous central areas, which may have contributed to a lack of stretching runs from Grigg and Massey as passes from deeper areas would prove extremely difficult.

Wigan’s 7-0 drubbing of Oxford may also provide insight into why Latics have maintained excellent form away from home. Teams generally play more openly at home as opposed to sitting in a low block, and Wigan clearly excel when they have large spaces to work with. Jacobs, Powell, Grigg, and Massey provide a strong threat on counter attacks, coupled with Evans’ range of passing. Although all things point to Wigan being the best team in League One, be it the league table or underlying performance metrics, they will have to improve against teams that set up to defend for a point, of which we can assume the majority of teams visiting the DW will look to do from hereon in.

Caldwell stuck to a three-man defence, though, and his decision to bring on Craig Davies rescued a point for the home side. As the game went on and Birmingham began to sat deeper, Wigan pushed for an equaliser but also looked quite fatigued. For a five minute spell, Wigan were playing in a 3-1-2-4 shape, with Powell joining Grigg up front, Wildschut and Jacobs playing extremely high and wide, and Power sitting behind Gilbey & MacDonald. This shape meant that Wigan were able to sustain pressure on Birmingham’s defence due to having better spacing and thus a faster, more effective circulation was possible, but the away side still closed important spaces. Wigan’s tiredness showed as their midfield struggled to continuously support attacks, which led to Caldwell changing strategy. Ultimately, the introduction of Davies meant both of Birmingham’s centre back were simultaneously occupied for the first time in the match, which led to the sub sneaking in at the back post to score a deserved goal.

Caldwell stuck to a three-man defence, though, and his decision to bring on Craig Davies rescued a point for the home side. As the game went on and Birmingham began to sat deeper, Wigan pushed for an equaliser but also looked quite fatigued. For a five minute spell, Wigan were playing in a 3-1-2-4 shape, with Powell joining Grigg up front, Wildschut and Jacobs playing extremely high and wide, and Power sitting behind Gilbey & MacDonald. This shape meant that Wigan were able to sustain pressure on Birmingham’s defence due to having better spacing and thus a faster, more effective circulation was possible, but the away side still closed important spaces. Wigan’s tiredness showed as their midfield struggled to continuously support attacks, which led to Caldwell changing strategy. Ultimately, the introduction of Davies meant both of Birmingham’s centre back were simultaneously occupied for the first time in the match, which led to the sub sneaking in at the back post to score a deserved goal.